“I had told you I did not print” —Emily Dickinson to T. W. Higginson (L316)

“Flowers – well, if anybody” (Fr95) as published in the Springfield Republican

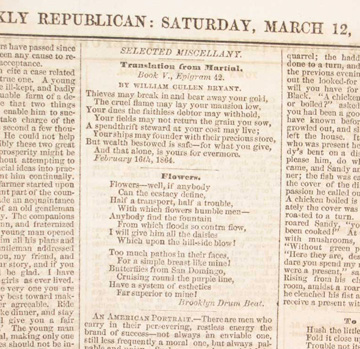

Did Emily Dickinson want to publish her poetry? No one knows for sure. Throughout her life, her work circulated among family and friends, some of whom had influence to shepherd a few poems toward publication. Between 1850 and 1866, ten Dickinson poems appeared in newspapers, all anonymously and probably without her knowledge. (Poems published in Dickinson’s lifetime can be found here.)

Late in the poet’s life, public awareness of her work increased. Helen Hunt Jackson, the well-known author, successfully finagled Dickinson’s “Success is counted sweetest” into A Masque of Poets (1878), a collection of anonymous verse to which Jackson also contributed. Jackson scolded Dickinson for refusing to publish: “You are a great poet—and it is a wrong to the day you live in, that you will not sing aloud” (L444a).

Subsequently Thomas Niles, publisher of Masque, broached the subject of publishing a collection of her poetry. Dickinson avoided giving an answer. Around the same time, in 1880, an Amherst charity approached her for poems to “‘aid unfortunate Children.’” Uncharacteristically, she did not reject the possibility outright. Instead, she “hesitated” and then selected several poems for consideration. It remains unclear whether the poems were ever published.

Questions related to publishing Dickinson’s work became much more complicated after her death, when her sister Lavinia discovered a large collection of manuscripts (now known as the fascicles) that Emily had never mentioned. The dramatic story is fraught with emotional intensity, differing loyalties, and personal sacrifice. To learn more, see The Posthumous Discovery of Dickinson’s Poems.