“my Tutor”

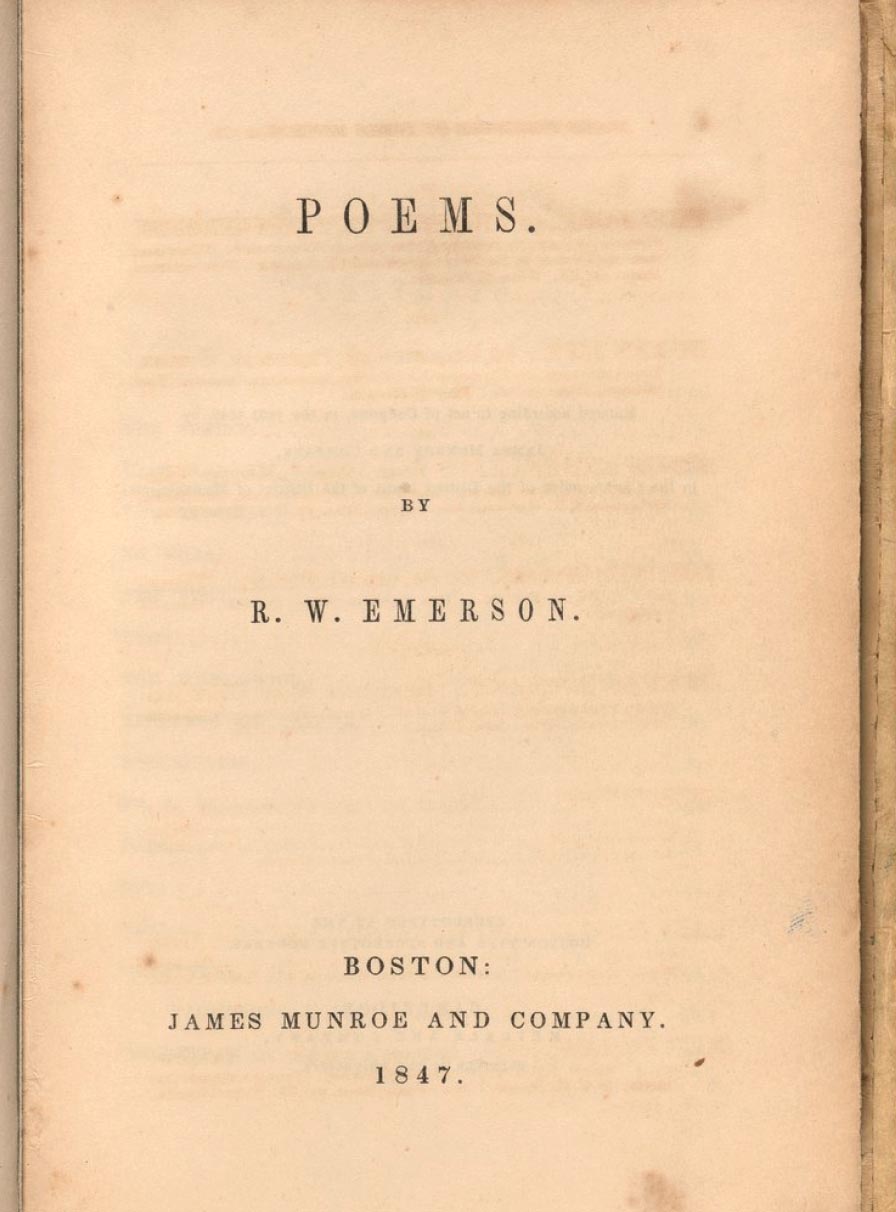

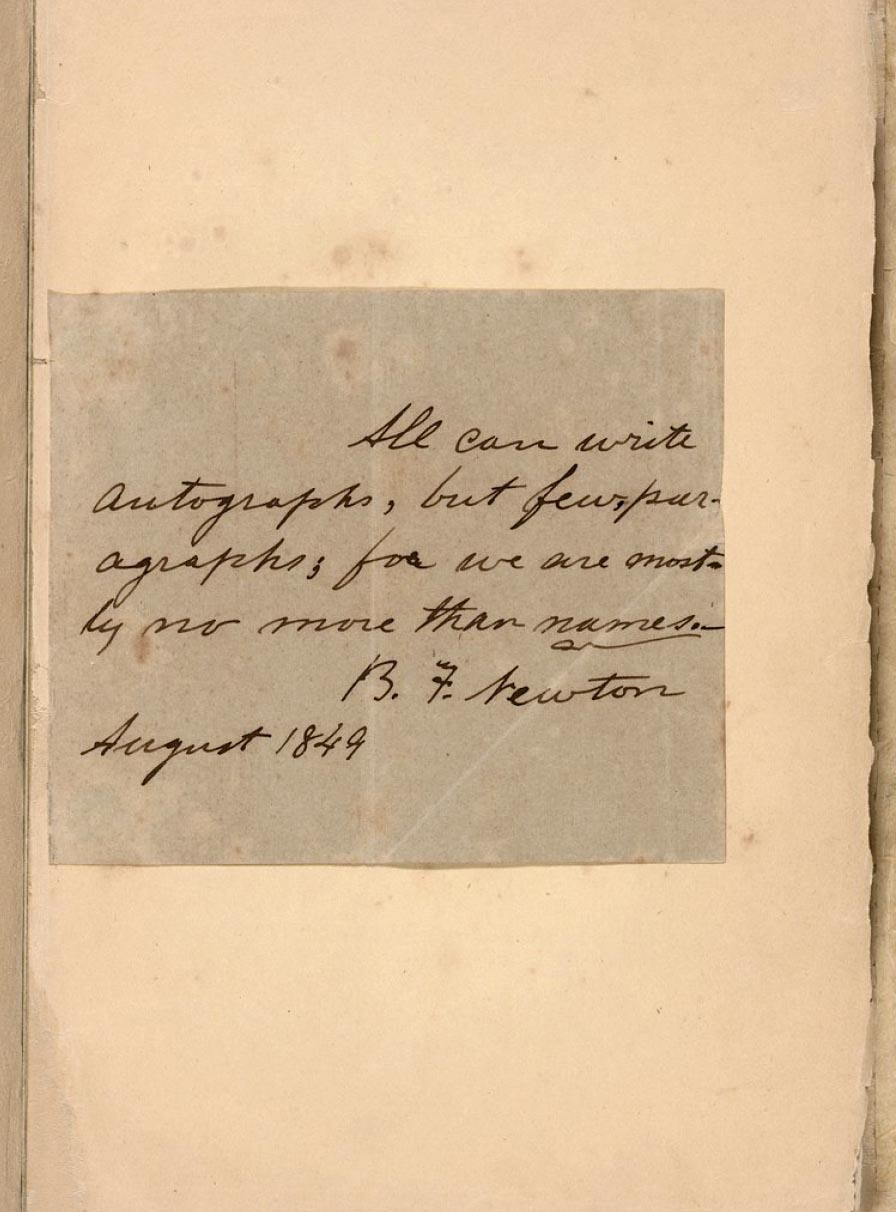

Introducing herself to a new literary correspondent Dickinson shared, “When a little Girl, I had a friend, who taught me Im-mortality – but venturing too near, himself – he never returned – Soon after, my Tutor, died – and for several years, my Lexicon – was my only companion” (L261). The “Tutor” is likely Benjamin Franklin Newton (1821-1853), a young man whose effect on Dickinson’s development as a poet was early and profound. Newton came to Amherst in 1847, as a law student with her father’s office. Newton became a familiar presence in the household, often partaking of family meals. Dickinson wrote, “Mr. Newton became to me a gentle, yet grave Preceptor, teaching me what to read, what authors to admire, what was most grand or beautiful in nature, and that sublimer lesson, a faith in things unseen” (L153). In the edition of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Poems he gave her, Newton inscribed to Dickinson, “All can write autographs, but few, paragraphs; for we are mostly no more than names. - B.F. Newton August 1849”

Emily Dickinson to T. W. Higginson (L261), April 25, 1862, in The Letters of Emily Dickinson, ed. Thomas H. Johnson (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1958), 2:404.

Emily Dickinson to Edward Everett Hale (L153), January 13, 1854, in The Letters of Emily Dickinson, ed. Thomas H. Johnson (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1965), 1:59.

Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University

Emerson, born the same year as Dickinson’s father, was a writer whose path very nearly crossed Emily Dickinson’s several times. He lectured at Amherst College between 1855 and 1879, often visiting and sometimes lodging at The Evergreens. It is unclear if Dickinson ever attended his speaking engagements or visited next door while he was there, but his presence evidences the younger poet’s access to the world of published writers. One of the few poems Dickinson consented to have published during her lifetime, “Success is counted sweetest,” was printed anonymously in her friend Helen Hunt Jackson’s anthology, A Masque of Poets, in 1879. Some mistakenly attributed this paradoxical poem about desire to Ralph Waldo Emerson (Leyda, 307).

Thomas Niles to Emily Dickinson, January 15, 1879, in The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson, ed. Jay Leyda (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965), 2:307.

Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University