Ned Dickinson

Ned Dickinson

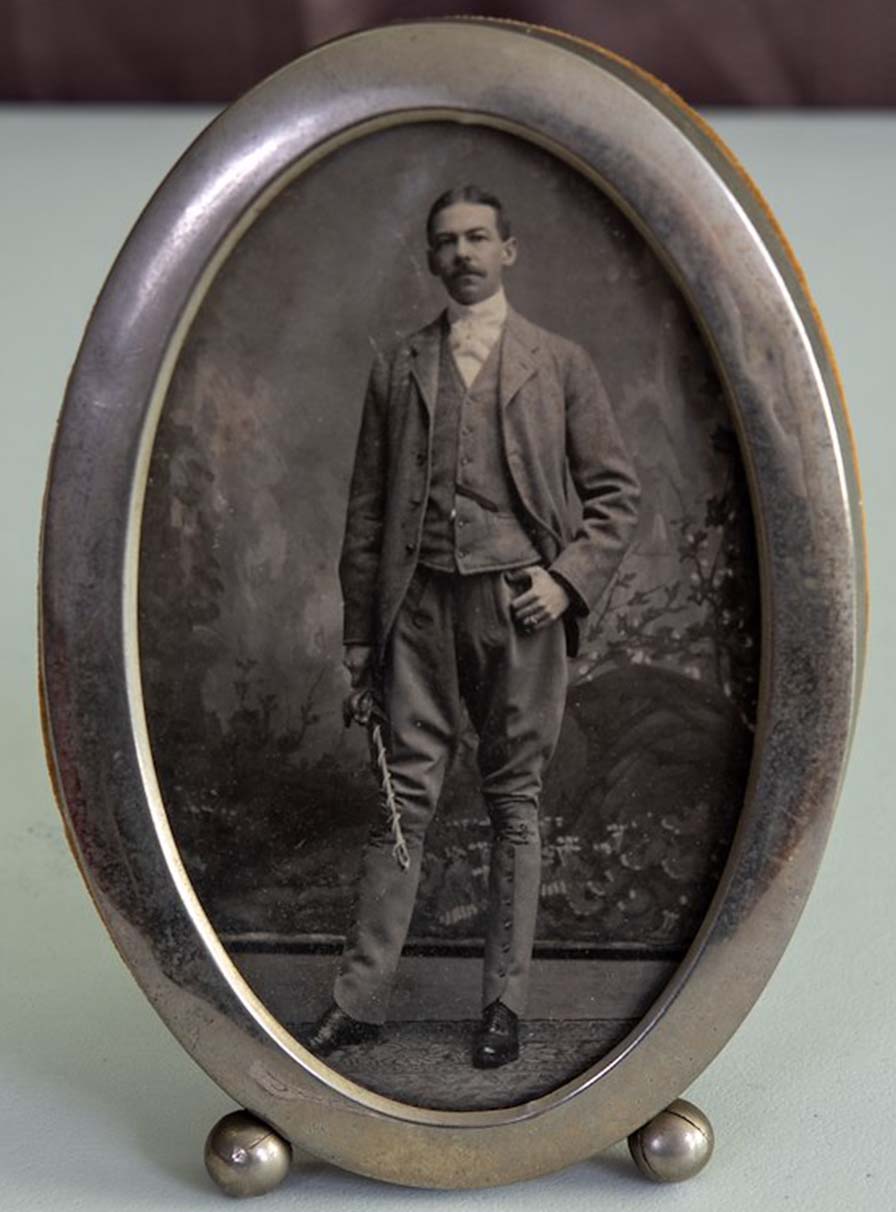

Austin and Susan Dickinson’s eldest child was born on June 19, 1861. Emily Dickinson had a close and playful relationship with the child named Edward (“Ned”) after his grandfather, and the two shared a pleasure in witty wordplay. “Ned tells that the Clock purrs and the Kitten ticks. He inherits his Uncle Emily’s ardor for the lie,” Dickinson crowed in a letter when Ned was not yet five. Claiming to prefer his pipe and Emerson to church when he grew up, it’s clear that aunt and nephew had much in common; he would later become an assistant librarian at Amherst College. Sadly, Ned suffered from a host of health issues including epilepsy and died young.

Emily Dickinson to Elizabeth Holland (L315), early March 1866, in The Letters of Emily Dickinson, ed. Thomas H. Johnson (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1958), 2:449.

Emily and Ned

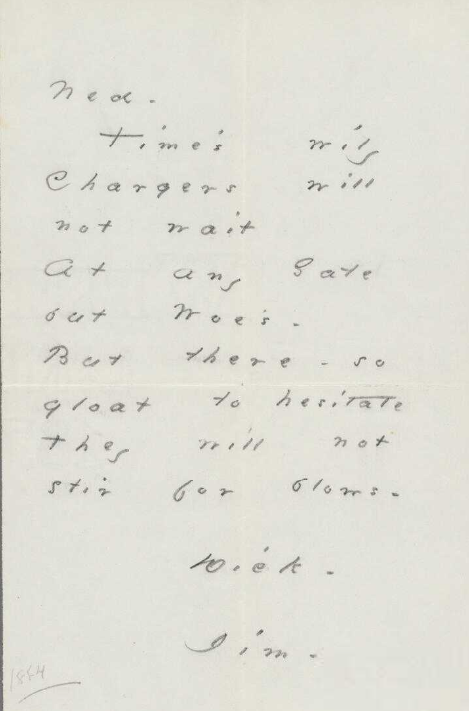

Ned — / Time's wily Chargers will not wait / At any Gate but Woe's — / But there — so gloat to hesitate / They will not stir for blows — / Dick — / Jim —

Phoebus - "I'll take the Reins." / Phaeton.

Dickinson wrote this witty pair of letters to Ned when he was in his late teens. The first teases Ned for losing control of his horses, Dick and Jim. The other was written a year later, after Ned’s father got a new horse. She referenced the prior incident in a quip, alluding to the Roman myth of the sun god Phaeton and his son Phoebus. In the myth, Phoebus requests to drive the sun chariot for a day but is unable to control the horses, scorching the earth and causing catastrophe. Dickinson addresses Ned as if she is his father, asserting that she’ll take the reins since he has shown he is an incapable driver.

Through these and other letters Dickinson sent Ned throughout her life comes through the pair’s shared traits—their wittiness, literary interest, devotion to Sue, and similar attitudes of religious unorthodoxy (Ned often referred to himself as the prodigal son, and the pair would jest about being sinners.) It’s clear that they had a special relationship, one playful and affectionate.

Correspondence from Emily Dickinson to Ned Dickinson (L604), about 1879, in The Letters of Emily Dickinson, ed. Thomas Johnson (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1958, 2:641.

Correspondence from Emily Dickinson to Ned Dickinson (L642), mid-May 1880, in The Letters of Emily Dickinson, ed. Thomas Johnson (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1965, 3:661.

Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University

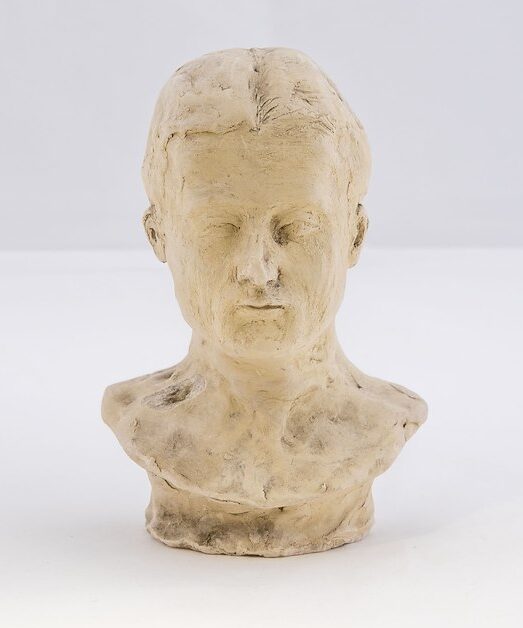

Ned's Death

Near the end of his life, Ned Dickinson, Emily Dickinson’s nephew, became engaged to Alice (Alix) Hill, who sculpted this plaster bust of him. With the bust’s fingermarks from sculpting and attention to detail, it is clear that Alix truly cherished him. But Ned never got to marry his fiance: in 1898, he experienced an attack of angina and died suddenly at 36 years old.