By Kate Smith, Emily Dickinson Museum 2023 Summer Intern

Throughout her writing years, Emily Dickinson sent her poems to more than forty correspondents, including Susan Dickinson, her posthumous editor Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and other friends and family. Occasionally, Dickinson sent gifts to accompany her poems. Sometimes these items overtly corresponded with the verse, and sometimes the connections were more sly or cryptic. Most gifts recorded were presumably from Dickinson’s garden or conservatory – she sent roses, jasmine, pine needles, and oak leaves, among other plants. Fascinating highlights from her gift correspondence include a dead bee sent to her nephew Gib, a cricket sent to Mabel Loomis Todd, and a pair of knitted garters sent to Catherine Scott Turner.

Given Dickinson’s interest in the writings of contemporary transcendentalists, scholar Daniel Manheim suggests Dickinson might have followed the advice of Ralph Waldo Emerson in his essay entitled Gifts: “The only gift is a portion of thyself.” Emerson refers to the ideal gift as a “piece of intelligence” – a representation of the giver’s art or talent. For Dickinson, gifts from her garden and from her kitchen were gifts of talents – as were her poems themselves. Manheim argues that Dickinson’s true gift was not the material object, but her infusion of verse, illustration, or creativity that transformed it into something different. This combination of a symbolic object and written word allowed Dickinson to truly send a piece of herself to her correspondents.

Daniel Manheim, “‘And row my blossoms o’er!’ Gift-Giving and Emily Dickinson’s Poetic Vocation” The Emily Dickinson Journal 20, no. 2 (2011): 4.

Featured Poems

- “When Katie walks” (Fr49)

Catherine Scott Turner Anton knew Susan from their time at the Utica Female Seminary; Susan hosted her at The Evergreens for about two months in early 1859. There, Kate met Emily, and greatly enjoyed the Dickinson family’s company. For the next few years, Anthon and Dickinson exchanged letters, sometimes including flirtatious sentiments. In the later portion of their correspondence, Dickinson sent this poem to Anthon with a pair of garters she knitted herself.

Franklin, 100.

Alfred Habegger, My Wars Are Laid Away In Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson (New York: Random House, 2001), 373-375.

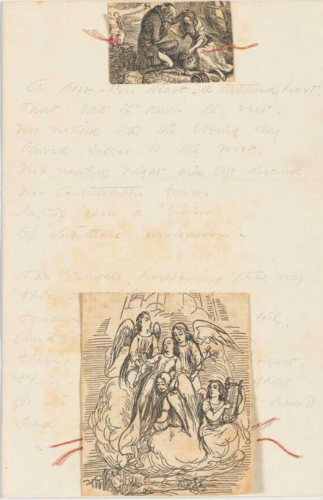

Emily sent this poem to Susan Dickinson in 1859. Accompanying the poem were two pictures cut out of Edward Dickinson’s copy of Charles Dickens’s Old Curiosity Shop.

Franklin, 165.

- “Of Brussels – it was not” (Fr510)

In 1863, Emily sent this poem to her cousins, Louisa and Frances Norcross, with a pine needle.

Franklin, 520.

Emily sent this poem to Mabel Loomis Todd in 1883 along with a cricket wrapped in paper. Dickinson had sent the poem to numerous others, referring to the poem itself as “My Cricket,” but only Todd received the insect, itself.

R.W. Franklin, The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University, 1998), 832.

- “A Field of Stubble – lying sere” (Fr1419)

In February of 1877, Ned Dickinson, the son of Austin and Susan and Emily’s nephew, had an epileptic seizure. He recovered within two weeks but gave his family and their acquaintances a scare. To cheer him, Emily sent him this poem, maple sugar, and a letter that read “I send you a Portrait of the Parish, and the first Sugar – Don’t bite the Parish, by mistake, though you may be tempted -” (L493).

Franklin, 1238.

Jay Leyda, The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson Volume 2 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960), 267.

- “The Savior must have been” (Fr1538)

Circulated to various correspondents, Dickinson sent this poem to The Evergreens (to Austin and Sue Dickinson) along with an iced cake at Christmastime in 1880. In one of her correspondences with Thomas Wentworth Higginson, she called the poem “Christ’s Birthday.”

Franklin, 1345.

- “His little Hearse like figure” (Fr1547)

Emily sent this poem along with one of her most intriguing gifts – a dead bee – to her nephew Gib in 1881 when he was six years old. Dickinson titled the poem “The Bumble Bee’s Religion,” and began the note with the lines “For Gilbert to carry to his Teacher –.” At the conclusion she wrote:

“All Liars shall have their part” –

Jonathan Edwards –

“And let him that is athirst come” –

Jesus –

The poem, a celebration of “idleness and Spring,” was sent in response to the teacher’s punishment of Gib for his insistence that a beautiful white calf was living in their attic.

Franklin, 1355.

Alfred Habegger, My Wars are Laid Away in Books, 549.

Thomas H. Johnson, The Poems of Emily Dickinson (Cambridge, MA: Belknap PRess of Harvard University Press, 1955), 1049.

- “The Dandelion’s Pallid Tube” (Fr1565)

Sarah Tuckerman was the wife of noted Amherst College professor Edward Tuckerman. Dickinson and Mrs. Tuckerman were close friends, and Emily often sent poems to her. The letter that accompanied the poem, sent in November of 1881, referred to Elihu Root, a young professor at Amherst College and good friend of the Tuckermans, who had passed away the previous December. Dickinson sent pressed dandelions tied with a red ribbon along with the letter and the poem.

Franklin, 1369.

Leyda, lxxv.

- “He lived the life of Ambush” (Fr1571)

Samuel Bowles, Sr. gifted Emily a jasmine plant in Christmas 1864, which she cultivated for years, even beyond his death in 1878. In 1882, Samuel Bowles Jr. visited Susan and Austin in the Evergreens. In tribute to his father, Emily sent Bowles Jr. this letter along with flowers from the same jasmine plant. She wrote:

“A Tree your Father gave me, bore this priceless flower.

Would you accept it because of him”

She also adjusted the opening words to “Who abdicated ambush.”

Judith Farr, The Gardens of Emily Dickinson (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 42.

Franklin, 1376.